Water issues downriver in Jefferson County affect those upriver, too, impacting the economy, recreation and food

"Without water - no farms - no food."

With that simple statement, Jefferson County Commissioner Mae Huston emphasizes the importance of irrigation water for farms near Madras, in Jefferson County, where the seed industry, along with other crops, are the lifeblood of the rural community. Without adequate water supplies for farmers, she says the City of Madras would be crippled. Farms would shut down. Businesses would close. People would be forced to move, and as she put it, "Madras could become a ghost town."

As you drive along Highway 97 you'll see fields of carrot seed crops on both sides of the highway near Madras. As harvest time approaches, I spoke with several farmers, seed industry representatives, irrigation managers and others to get a sense of how important irrigation and the Deschutes River is to the region and to the economy of Central Oregon.

Agriculture: An economic engine in Central Oregon

While the Kentucky Blue Grass and parsley seed crops represent a sizeable economic driver for the region, the size and scope of the carrot seed industry cannot be over-emphasized. The crop, which takes 13 months to grow and harvest, is critical to Jefferson County.

"We supply 40 percent of the world's need for carrot seeds," says Mike Weber, managing partner for Central Oregon Seeds, Inc., located near the Madras airport. As I tour the plant, Weber shows a rack of seed that will be exported to other countries, worth millions.

Janet Brown, Jefferson county's representative for Economic Development in Central Oregon, says, "When you grow almost half of the world's carrot seed and about 75 percent of the U.S. carrot seed, that's a huge economic engine not only for Jefferson County and Central Oregon, but the world." In total, she estimates there's a $30 to $35 million ripple effect the carrot seed industry brings to Jefferson County.

"These seeds wind up in Holland, the Middle East, Japan and other countries where eventually carrots wind up on the dinner table," says Weber.

Michael Kirsch at Madras Farms takes pride in knowing he helps feed the world. "It's neat to know that you as a farmer are producing something that ends up a long way from where it was grown and ultimately on someone's dinner table."

The combination of warm weather during the day and cool nights make Central Oregon an ideal location for growing carrot seeds. It's the premier growing region for this crop in the world, rivaled only by New Zealand.

But, it's dependent on the Deschutes River and how much seasonal irrigation water it can produce. That's of major concern to those in Jefferson County, as hot weather and dwindling water takes a toll.

The Deschutes is everything

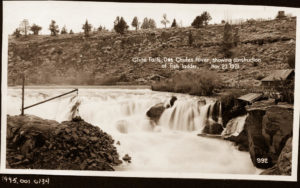

The source for the iconic river, and the irrigation it provides, is Little Lava Lakein the high Cascades, where snowmelt feeds the Deschutes system, eventually winding its way 252 miles north, to the Columbia River. Along the way it's joined by numerous tributaries such as the Fall, Crooked and Metolius Rivers—and others that help sustain water needs for not only farmers, but the diverse recreational and tourism industry that drives the economy in Central Oregon.

From Little Lava Lake, it's only a short distance before the river reaches Crane Prairie Reservoir and then Wickiup Reservoir, storing the irrigation water needed by farmers.

Look at current water levels in Wickiup and you'll see narrowing channels and miles of dry land where water covered it as recently as last spring and early summer. Reservoir levels have fallen to 22 percent capacity as of date of publication, according to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, with several weeks of irrigation needs still ahead.

While the reservoir, built in 1948 for irrigation, has fallen to near 10 percent capacity in other drought years, the red flag is waving for Jefferson County farms and irrigation managers this year.

"First and foremost on my mind is getting through this water year," says Mike Britton, general manager for the North Unit Irrigation District, supplying water to Jefferson County. "Our patrons are concerned about the level of Wickiup and how much water is available."

It also concerns EDCO's Janet Brown. "If agriculture were to dwindle without water, we would see storefronts close. You would see a huge impact on farmers and their families and the thousands of farm workers in the area," she says. In total, Jefferson County has about 450 farms, according to Brown.

Conservation becomes key

As water levels dwindle and more water is released during the winter storage months in order to protect the endangered Oregon spotted frog and fish, conservation has become more urgent.

According to Central Oregon Seeds' Weber, carrot seed farmers in Jefferson County have installed costly drip line irrigation systems to save water from evaporation on the thousands of acres growing the seed plant.

The Fox Hollow Ranch southeast of Madras is one farm with drip lines. After obtaining his graduate degree from Georgetown University and working for the Farm Bureau in Washington, D.C., for a decade, Kevin Richards returned to Madras to help operate the family ranch.

"The number one priority and concern for us is water," he says. "The amount of water dictates the crops that can be grown, how much can be grown and whether a farmer can grow a crop on every acre they own. It influences every aspect of our farming operation," he says.

Richards says one reason the carrot seed industry has thrived is because it can be efficiently produced through drip irrigation. "That helps save water, and the opportunity for efficiency is helping drive the industry."

While on-farm conservation measures are critical, so are measures now underway by the eight irrigation districts in Central Oregon.

The Central Oregon Irrigation District is the oldest and largest of those districts, with two canals supplying water to thousands of patrons. With the age of the canals, where evaporation and leakage occurs, modernization in the delivery system has also become critical to saving water, irrigation officials say.

Claims by advocacy groups that up to 50 percent of irrigation water is lost through evaporation and seepage isn't "too far-fetched, keeping in mind the calculated losses include river losses," says Britton of the North Unit Irrigation District. NUID water can travel 120 miles before it gets delivered to farms, he says.

During the past winter, COID completed piping 3020 feet of canal—at a cost of $5 million—in the Brookswood neighborhood of Bend, saving 5 cubic feet of water flow per second, now returned to the river. A cubic foot of water is equal to 7.48 gallons, so 5 cubic feet per second adds up to a lot of water.

"Every drop counts. To put it in perspective, we divert nearly 900 cubic feet per second between our two canals during the peak season," says Shon Rae, deputy managing director. "Our 20-year capital plan estimates between 150 and 200 cfs will be conserved through piping projects."

COID also has a much larger near-term piping project now in the planning stages. A $40 million construction project could start as early as fall of 2019 from Smith Rock to King Way in Redmond, conserving much more water than the Brookswood piping project—an estimated 37 cubic feet per second, according to Rae.

Long term, the irrigation districts are completing watershed plans to improve their delivery systems. Once that's accomplished, they can apply for federal matching funds that could amount to nearly $100 million for modernization, according to Britton, who also heads up the Deschutes Basin Board of Control which comprises Central Oregon's eight irrigation districts.

Collaboration

When environmental groups filed lawsuits, concerned with the health of the endangered Oregon spotted frog, Jefferson County farmers and others became worried if they would receive the water they needed for their crops.

Numerous advocacy and user groups such as the Coalition for the Deschutes, Trout Unlimited of Bend, the irrigation districts and others began encouraging intense collaboration to find solutions that would meet all needs. It wasn't an easy decision, but groups resolved to release more water from Wickiup Reservoir during the winter storage months to save the spotted frog.

Now, 100 cubic feet per second of water is released during the winter months, compared to releases of as low as 25 cfs in past years. For those working to save the frog, it's a beginning, but they note that more water needs to be released during the winter to fully restore the health of the Deschutes River.

"There's been a lot of collaboration and focus on the river due to the Endangered Species Act, exacerbated by the drought conditions we're in," says farmer Richards. "It's the number one priority for having a sustainable solution for all of Central Oregon whether it's recreation, tourism, municipal use or farming."

The collaborative process to seek mutual agreements, he maintains, is showing promise. "A lot of people are at the table and willing to discuss options so there is still water available so it doesn't put farmers like myself out of business."

The collaborative process has also received praise from opposite members of the political spectrum, including Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and Congressman Greg Walden (R-OR2).

Brown at EDCO-Jefferson County agrees the present collaboration is showing promise, but with a warning. "I think people south of us in Bend sometimes think that's just a Jefferson County issue and that they can get it worked out up there. It's not. It's an issue for all of us."

Her warning: "If you want to paddle board on the Deschutes in Bend, if you want to surf the rapids by the Colorado Bridge, you will need water. If we can't all come to the table and agree on the spotted frog issue and let all the users who need water have water, then you won't be able to do some of those things and that will really affect tourism in Bend."

The economic impact of outdoor recreation and tourism also can't be overemphasized. Tourism continues to be the single-largest industry in Central Oregon, employing more than 9,400 people and generating total economic impacts that exceed $1.19 billion annually, according to the Central Oregon Visitors Association.

And, with that economic reality, Brown not only urges more collaboration to seek solutions, but urges everyone who has a stake in the river to avoid lawsuits.

It would appear the irrigation districts and the Coalition for the Deschutes are cooperating. The Coalition and the Deschutes Basin Board of Control recently jointly developed and signed a memorandum entitled: "A Shared Vision for the Deschutes: Working Together so Families, Farms, and Fish can Thrive."

North Unit's Britton says, "There's a long list of issues we contend with on a daily basis, but at the end of the day, it's these crops that put food on the table."

Brown adds, "I think we can get there. Everyone's at the table. If we don't have any more lawsuits and everyone plays nice, then I think we'll get there."

Brian Jennings produces the Great Outdoors and other features for Central Oregon Daily seen on KOHD ABC at 6 pm and KBNZ CBS at 7 pm.